Screening: Saturday, April 6, 8 p.m. Rich Theatre

This Saturday we have our first film from world-renowned art cinema director and contemporary Mexican auteur Carlos Reygadas. At its 2007 release Silent Light won five Ariel Awards (Mexico’s equivalent to the Oscars), the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and many other international prizes.

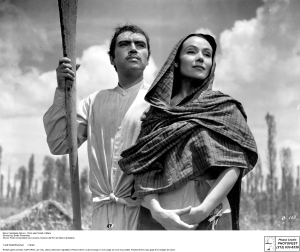

A story of a Mennonite family living in rural Mexico and the events and emotions that test the faith of the family’s patriarch, Silent Light is inspired by—one might even say it’s a remake of—Danish director Carol Theodor Dreyer’s 1955 film Ordet. Like its source material, Silent Light is organized around the problem of photographing, seeing, and believing in the transcendent. It’s part of the richly paradoxical tradition of religious-realist films, which combine a naturalist attention to “ordinary life” with capturing the spiritual world of divine happenings. There would appear to be an unavoidable friction between depicting everyday, material existence and portraying something like a divine miracle or any other event that belongs to a realm beyond proof, beyond material evidence, beyond the photographic image. How, after all, does one faithfully represent an intangible entity?

Silent Light gracefully delves into this contradiction, however, by evoking the transcendent through the everyday. In this movie we can never point to the existence of divine action, but ordinary objects—the human face, the ticking of time, the natural world, the simple turning over of a day—all this slowly bends toward evidencing the transcendent.

Famed film critic and theorist Andre Bazin wrote of Ordet, “Within this universe which is more conscious of mystery, the supernatural does not loom up from outside. It is pure immanence, revealed in its extremity as the ambiguity of nature.” Silent Light‘s beginning long-take of the sun rising and of the sun setting at film’s end exemplify the supernatural, pure immanence in the ambiguity of nature that Bazin see in Ordet. These scenes ask the viewer to meditate on the “everyday” quality of nature, while their spectacle and sheer beauty bespeak a daily miracle and call forth that most famous first miracle, “Let there be light.”

Indeed, sunlight inflects almost every moment of this film, and in its rare absence other natural forces present themselves. The skies open up and rain pours to take away a beloved wife and mother in a seemingly divine deluge, the echoes of which resound in the holy water that washes the film’s young and dead. We wade through hilltop prairies and watch the clouds roll in. Nature rains down, rises up, and shines upon us, performing something greater than its mere elements, and yet we can only consume its textural surface. It comes up to meet us at the very limits both of our senses and of the filmic medium itself, as sunlight refracts and separates through the camera’s vision and water splashes against the lens. These natural forces glimmer and soak our view, but there is no penetrating them to find some ultimate truth or some definitive image of a god; we can only receive them as they are and stare in wonder at the spiritual essence they may harbor.

Light and nature find a brilliant reprisal in the final, climactic miracle of Silent Light: a resurrection. The scene presents an ostensibly insurmountable challenge to a realist aesthetic, for with such an explicit invocation of a higher power, what other choice does a religious-realist film have but to fall back into the safe territory of pure representation—of finally picturing the undepictable force by which the transcendent occurs? But Silent Light once again finds a way to picture only pure immanence and faith in, not the factual existence of, the transcendent.

Dressed in stark white, the deceased lies amid pearly linens, her white coffin a lonely island in her immaculate surroundings. This last, white room seems to be a transitional space to the bright light flooding in through the windows, overexposed to spiritual excess. If it is God, natural light, or both that summons the deceased, it is also the natural world. Right before the miracle occurs, a character holds up her hand in a commonplace gesture to block the sun from hitting her eyes, but the camera lingers, her arm extended toward the heavens. A cut to a point-of-view shot shows her hand over the sun. Through sheer duration, this shot transforms a common gesture into a miraculous acceptance of grace from the heavens, a grace which she will pass on to the dead.

You’ll have to come to the screening to see what happens next. But I will say, in the end we have only a butterfly that flutters around the room before escaping through the window into nature; whether it is earthly existence or eternal bliss is left unspoken in the face of a slow sequence of landscapes that culminates in the last, dark sinking of the sun.

For tickets to the Saturday, April 6 screening of Silent Light go HERE.

![reygadas[1]](https://screensonhigh.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/reygadas1.jpg?w=213&h=300)

![Exterminating[1]](https://screensonhigh.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/exterminating1.jpg?w=300&h=228)